Possibilities and probabilities

One thing that beekeepers learn early on is that although it is possible to grow strong hives and get a decent honey harvest it is also possible to loose your bees and not get any honey. I’ve even heard it said that people get into beekeeping because of the bees and they get out of it because of the honey.

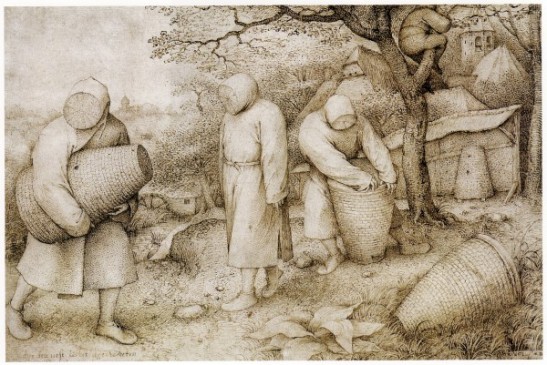

Fig 1. Honey is food for both body and soul.

How does anyone plan for such disparate eventualities? How do beekeepers gauge the probability of each possibility?

Small producers (10 hives or less) usually have a “real job” and don’t plan to make much money from their honey. They often give it away to friends and family and sell what excess they have (if any) through word of mouth.

Large producers (>100 hives) have enough hives in enough bee yards that they’ve increased the likeliness that their overall production with be close to average production. The more hives you have the less likely it is that all of your hives will go kaput and the more likely you’ll be to have the capacity to store extra honey to cover low production years. These larger producers are also large enough to afford the costs associated with advertising, marketing at farmer’s markets and independent retail chains so they can get that premium for their products.

I’ve talked to a few mid-sized honey producers (between 30 to 99 hives) and many of them rely on the wholesale honey market to supplement their direct sales in bad years and to buy their excess in the event of a bumper crop. This means that customers are not necessarily getting the honey they believe they are buying (as the only name required on the jar is the name of the “packer” not the producer). This is not to say that all local producers use the wholesale market; one producer I spoke with just sells whatever he’s able to harvest and resigns himself to earning less in the bad years.

This reliance on the wholesale market also means that in a good year the producer is selling their honey at a discounted price instead of capturing the full price that customers would be willing to pay. According to Statistics Canada CANSIM data Table 001-0007 there were 3,150 beekeepers in Ontario last year with an average of 31 hives per beekeeper. The average price for the honey sold was calculated to be only $2.33/lb (around $5/kg). I know of a larger scale beekeeper in the Ottawa-Gatineau area that doesn’t market his honey and only sells it to wholesale buyers. Just think of the money he could be earning if he was actually selling his honey to consumers.

Boring Billy Bee Honey retails for around $6 per 500g ($12/kg) and strangely enough the tasty local stuff that is being marketed to Ottawa consumers is priced between $10 and $13 a kg. Did you hear that folks? Local producers are selling their honey at prices lower than Billy Bee! WHY then are people still buying Billy Bee?

Fig 2. Billy Bee bottle

Most grocery stores are part of a supply chain that is structured around a “plan-O-gram” which dictates which products go on which shelves and involve distribution of those products from single-source places like Toronto. The logistics of getting a product onto chain retail shelves is likely beyond the capacity of any of our local producers (even the big guys). It would mean co-ordination of enough producers to regularly supply the retail demand for “local” honey at the provincial level, label and package it in a way that would be satisfactory to chain’s demands, and deliver it to the distribution center in Toronto. Not to say that it’s not possible; just that it’s not probable.